Good morning, Fringe readers!

I forgot that researching The Open courses always takes a little extra time and wasn’t able to put together a winning lineup review, so it’s just an abbreviated version of The Fringe this week.

“Abbreviated” is a bit of a misnomer, however, since this edition is still over 5000 words. Let’s not waste anymore and get right into it.

The Future

The best golfers from across the globe will converge on Northern Ireland for the final major of the year, the 153rd playing of The Open Championship at Royal Portrush Golf Club.

A contingent of PGA Tour and DP World Tour golfers will also be in California for the Barracuda Championship at the Tahoe Mountain Club in Truckee. Like every week with an alternate field event, I will just focus on the main event.

The Open was founded in 1860, making it the oldest golf tournament in the world. Outside of a couple of world wars, it has only been cancelled twice; once in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and once in 1871 because there was no trophy to give to the winner.

Traditionally, it is always held at a coastal links course. Not only are links courses the predominant style of course in the United Kingdom, but they are considered to be the original style of golf course. The tournament is as much a tribute to the origins of the game as it is the most prestigious challenge for the modern golfer.

The location of The Open changes each year, rotating among a set of courses in England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. A total of 14 courses have been used throughout the history of the tournament, but there are currently 10 courses in The Open rotation.

The first Open Championship was played in October, but it was moved to the middle of July at some point (I have not been able to find the exact year). In 2019, when the PGA Championship was moved to May, The Open became the final major of the season, a more fitting spot for the historic tournament.

The winner of The Open Championship is referred to as "The Champion Golfer of the Year" and is awarded the Golf Champion Trophy and a gold medal. The first winners of The Open were given the Challenge Belt, but after winning The Open for the third time in 1870, Young Tom Morris was given the belt to keep for good. Prestwick Golf Club, the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews, and the Honorable Company of Edinburgh Golfers agreed to split the cost of a new Golf Champion Trophy. The new trophy would eventually be known as the Claret Jug. The Claret Jug wasn’t ready for the 1872 Open, so the winner, Young Tom Morris again, was awarded a gold medal. The gold medal has since been awarded to the winners of The Open as well.

The tournament is organized by the R&A and is co-sanctioned by the PGA Tour, DP World Tour, and Japan Golf Tour

Like the other majors, the list of Open Championship winners is a pantheon of the greatest in the game. The early years were dominated by Old Tom Morris and Young Tom Morris. Another father-son duo, Willie Park Sr. and Jr. also claimed multiple titles in the early years. Harry Vardon then took over, winning his 6th Open Championship in 1914. Bobby Jones and Walter Hagen each won multiple times in the following years. After World War 2, the names Snead, Locke, and Hogan were inscribed on the Claret Jug. Then came the triumvirate of modern legends: Player, Palmer, and Nicklaus. Tom Kite, Seve Ballesteros, and Nick Faldo all won it multiple times. The People’s Champ, John Daly, won at St. Andrews in 1995. And no list of legends would be complete without Tiger Woods, who got his third Open win in 2006.

Last year at Royal Troon, Xander Schaufele battled wind and rain in the final round to secure his second major title of the season with a two-shot victory over Justin Rose and Billy Horschel (winning score: -9; cutline: +6).

Here are the last 10 winners and their scores:

The field

Like the U.S. Open, there are multiple ways of qualifying for The Open Championship, including ways to play your way into it. There are the regular pathways like prior performance at The Open Championship, performance at other majors, and OWGR. There is also the Open Qualifying Series; 11 tournaments across the globe in which the highest finisher not already exempt gets in. Also, any scratch male golfer or female golfer can attempt to gain entry through local and final qualifying, the British equivalent to golf’s longest day in the United States.

The Open and the U.S. Open usually contend for the second strongest field in all of golf each year after the PGA Championship. Last year, however, The Open claimed the title of strongest field in all of golf with a strength of 487 (strongest of 44 tournaments; average was 275.6).

The field is set for 156 golfers. The last three spots will be awarded to the top three finishers from the Scottish Open that are not already exempt.

There is no doubt that The Open Championship will once again host one of the strongest fields in golf. The only question is how it will rank among the other marquee events. There are 49 of the top 50 golfers in the world in the field. Billy Horschel is the only top 50 golfer skipping the event as he recovers from hip surgery.

Here is the link to the full field.

Course Description

Royal Portrush Golf Club is a private club located on northern tip of Northern Ireland. It lies on the coast of the Northern Channel, a body of water connecting the Irish Sea to the rest of the North Atlantic and is named for the nearby town.

The club was founded in 1888 and is home to two courses, the Valley Links course and the Dunluce Links course, and a six-hole pitch-and-putt course called the Skerries (a chain of islands visible from the course). The Dunluce Links course, named for an old castle overlooking the property, is used for championship play.

The Dunluce Links course was designed by Harry Colt and opened in 1932. It has hosted two Open Championships, once in 1951 and then in 2019. The event in 1951 was the first time that the Open Championship was held outside of Scotland or England. Portrush is still the only course outside of England and Scotland to be used for the championship.

The first Open Championship at Portrush was won by Englishman Max Faulkner at -3 (when par for the course was 72).

In 2019, Shane Lowry took a four-shot lead into the final round and cruised to a six-shot victory over Tommy Fleetwood (winning score: -15; cutline: +1; median score for cutmakers: +1).

The course also hosted the 2012 Irish Open won by Jamie Donaldson at -18.

Like any course that has been around for almost a century, it has seen its share of changes. We’ll focus on the most relevant, however. Ahead of the 2019 Open Championship, the 17th and 18th holes were replaced by new holes built on land from the Valley Links course. Most of the holes were remodeled and bunkers were added throughout the course. The changes resulted in the course being lengthened by 201 yards.

Additional work was done to the course ahead of this year’s championship. There is a new championship tee on the fourth hole, the front left portion of green on the first hole was adjusted to allow for an additional pin location, and the green on the 7th hole was rebuilt to soften the contours.

The Dunluce Links course is now a 7,381-yard, par-71 coastal links design. By par, it is the 17th longest course on tour this season (out of the 49 courses I’ve done the calculations for).

The course was built on the bluffs overlooking the Atlantic Ocean that are occupied by large sandhills covered in vegetation. The fairways snake their way through the natural valleys created by the hills and dunes, and the greens blend seamlessly into the into the landscape. The result is a layout with stunning views of surrounding hillsides and the ocean marked by various islands.

It has most of the hallmarks a classical links course; it’s coastal, has sandy soil, fits seamlessly into the natural topography, is firm and fast from tee to green, has undulating fairways, has a mix of pot bunkers and deep bunkers, long, penal rough, and the weather plays an outsized role in how the course will play. One notable exception is the green complexes; the greens at most links courses are level with the fairways, making the ground game an important factor, but many of the greens at Portrush are elevated, meaning ariel approaches will be important. Also, while there are 57 bunkers on the course, a much lower proportion of them are the dreaded pot bunkers.

The course has the standard four par 3s, eleven par 4s and three par 5s. In 2019, despite the tough scoring, there were six holes that played under par. The three par 5’s were the best scoring opportunities on the course, as usual. The next best scoring opportunity was the 372-yard par 4 5th hole with a corner that can be cut, making it a drivable par 4 for the longest hitters. The shortest of the par 3s that played under par, and the 446-yard par-4 10th hole played a hair under par. The par 3s range from 176 yards to 236 yards. Aside from the short par 4, there are six par 4s in the 401-450 range, three in the 451-500 range, and one that is just over 500 yards in length. The par 5s are 532, 575 and 607 yards in length. The short par 5 is reachable by most, but it’s wise to play the other two par 5s as three-shot holes considering their length. Golfers that risk going for the long par 5s in two could be rewarded with a birdie, but there is also a good chance that they end up in a deep bunker and are lucky to get away with par.

Here is the 2025 scorecard:

Off the tee, golfers will see narrow, undulating fairways that serpentine their way through the sandhills and dunes (average width is 27 yards). The landing zones are protected by deep bunkers, pot bunkers, mounds, and thick fescue rough. In true links style, the bunkers are truly penal; golfers will most likely be unable to advance their ball towards the green from the bunkers and will just be playing to get their ball back in the fairway. Also, instead of being outside of the fairway lines, there are a number of bunkers right in the middle of the short grass. The rough is a mix of fescue, bentgrass, indigenous grasses and wildflowers. There is a two-yard strip of rough directly adjacent to the fairway that will be two inches in length, but it becomes a thick tangle of brush, fescue, and tall grasses beyond that. The fairways are fescue as well. In fact, the rest of course is wall-to-wall fescue. There is a stream that comes into play on two holes, but I’ve seen some debate as to how in play it actually is. There are two holes (the 1st and 18th) that feature internal out-of-bounds in play, and five holes in all with out-of-bounds in play. There are many doglegs that will challenge golfers mentally, asking them to take on the risk of cutting the corner or laying up to a safer section of the fairway. There is a difference of 20 m between the highest and lowest points on the course, and golfers will climb a total of 78 m during their rounds. The elevation changes create dramatic uphill and downhill holes (the par-3 13th hole drops 100 feet from tee to green), and a few blind tee shots. It’s also used to create some tilt in the fairways that are contoured to feed balls into bunkers, so golfers will have to control their trajectories to avoid rolling into one of the bunkers.

On approach, golfers will see small, undulating greens with lots of slope that are tucked in amongst the giant dunes (average green size is 5,400 sq. ft.). The putting surface is fescue. Although most of the course will be firm and fast (unless the weather steps in to change that), the greens are expected to be slow (10 on the stimp). They are protected by thick rough, bunkers, steep drop-offs and all sorts of bowls, basins, humps, hollows, moguls, and grassy hummocks. Some of the greens play in the classic links fashion; they are level to the fairways and the fronts are open. Other greens, though, are elevated and feature false fronts, steep runoffs, and collection areas. Most of the elevated greens are also tapered in every direction. Golfers will have to have superb control over their spin and flight of the ball. The greens also rely on the various forms of undulation for protection, including knobs, ridges, tiers, folds, and swales, just to name a few.

The 1951 Open Championship was obviously in the days before advanced analytics, and we only have limited data from the 2019 edition. Driving Accuracy was 58.2% and Good Drive Percentage was 78.1%, both of which are a couple of points below the tour average. The Scrambling Percentage was 79.1% (tour average was 57.4%). We also have Strokes Gained: Off the Tee and Approach data, but without the Around-the-Green or Putting data, they are somewhat limited in their usefulness (Shane Lowry led in both). Driving Distance data is also available, though I don’t see the raw numbers, just the Driving Distance Gained data. Driving Distance does not appear to be too beneficial; only one golfer in the top ten in distance (Tyrrell Hatton) was also in the top ten overall. Due to numerous doglegs, penal rough, and diabolical bunkers, golfers are clubbing down to try to keep the ball in the fairway, so Portrush simply isn’t a driver heavy course.

We also have Strokes Gained data by hole type. Only three golfers in the top 20 gained strokes in all four par 3 distance buckets and half of the golfers in the top ten were also in the top ten in scoring on the par 3. I take this to mean that golfers can’t win the tournament on the par 3s, but they shouldn’t give too much away either. The par 4 data suggests that you have to take advantage of the short par 4 and you have to make some hay on the 400-450 par 4s. The other ranges don’t appear to be too important. Only a few golfers separated themselves on the par 5s, and they all ended up tied for 20th. Everybody in the top ten gained strokes on the par 5s though, so you have to do a little bit of scoring on them to contend.

There were also a couple of interesting notes from Geoff Shackelford in his newsletter The Quadrilateral. Shane Lowry only hit 62.5% of fairways; better than average but nothing overwhelming. Shane Lowry also led the way by hitting 57 greens in regulation while there were only 12 other golfers that hit more than 50, suggesting that Greens in Regulation is the key to success at Royal Portrush.

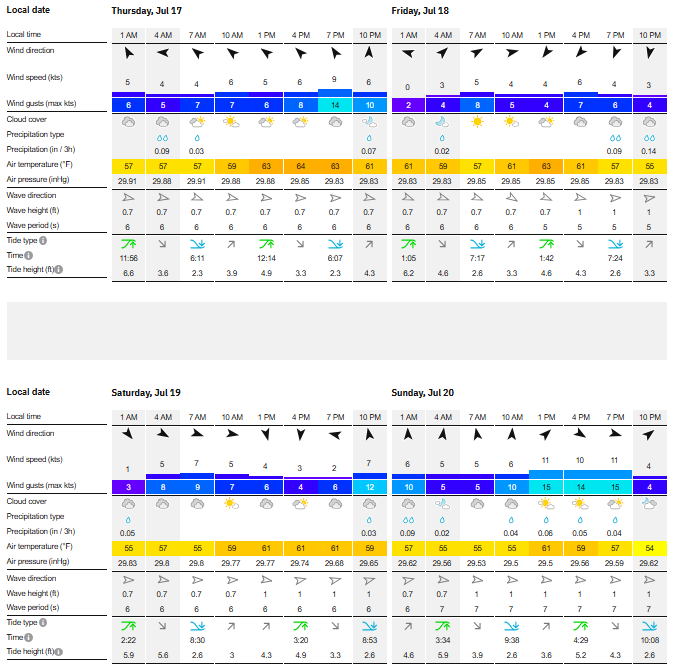

The Weather

As with all links courses, the weather is going to play a role this week, particularly the wind. The winds are hard to predict, however. As a coastal course, they are almost always blowing, the trick is figuring out how hard they will blow. Forecasts will change with each update and projected wave advantages have been known to switch once the tournament starts.

The rain can have an impact too. Links courses typically play firm and fast from tee to green (the greens are kept a little longer than standard American courses to slow them down and prevent balls from rolling off in high winds). Rain can soften the course, making greens more receptive and limiting the rollout in the fairways.

While the area has enjoyed a warm and dry start to the summer, it looks like the weather is reverting to the cool and rainy weather we typically associate with the area. There is rain forecasted for almost everyday of tournament week, and highs will be in the 60s with mostly cloudy skies. The winds will be in the single digits for most of the tournament except for a couple of brief periods with gusts over 10 mph.

I expect this forecast to change throughout the week, so I will be paying close attention to each update.

DFS Strategy

I will run through the usual metrics we use to determine how much bankroll we should use this week, but let’s be honest, it’s the final major of the year, we’re not holding anything back now.

We actually don’t have any data on penalty strokes or reloads, so we can only speculate on this metric. I’m torn, however. There is almost no water on the course, but there are five instances when O.B. comes into play. I can’t imagine there are many reloads and penalty strokes but there will be some. I guess it’s somewhere in the middle and shouldn’t impact our decision on how much to play.

The chalk has a mixed past at The Open. The past two winners of The Open weren’t the highest-owned golfers in their range, but they could certainly be considered chalky. The chalk can struggle though; Rory McIlroy, Ludvig Aberg, Tommy Fleetwood, and Tony Finau were some of the notable busts last year and ten golfers above 10%-owned missed the cut. The previous year, there were almost no notable golfers that missed the cut with just three golfers over 10%-owned missing the cut, and only Dustin Johnson was above 13%. I would say that’s inconclusive.

The cumulative ownership of winning lineups over the past two years has fluctuated wildly. Two years ago, they ranged from 52% to 63%; suggesting you had to go far out on the risk curve to be successful. Last year, the winner of the Birdie had a cumulative ownership of 91.1%, which is well above the range we typically shoot for, suggesting you did not need to go out on the risk curve at all. Again, inconclusive.

The factor that would give me pause though is the weather. Wave advantages can pop up out of nowhere. Even when we think we have a good bead on the weather, it has been known to change completely. Golfers that regularly play The Open are accustomed to the misfortune of being on the wrong side of the draw, but it’s extremely frustrating for golfers and DFS players alike. I wouldn’t let this impact my decision on how much bankroll to commit, however. We can always protect ourselves against an unexpected flip flop by stacking both waves. You don’t have to go full stacks for every lineup but one or two from each wave will safeguard ourselves from being completely dead before the weekend even starts.

We were going to play our usual bankrolls anyways, but I don’t really see a reason to hold back. In fact, due to the inflated prize pools associated with a major championship, I don’t mind if you play a little extra.

As the final major of the year, contests sizes are going to explode. DraftKings will run its full slate of contests; double-ups, 50/50s, single-entry contests, GPPs, and Millionaire Makers. There are two Milly Makers, one with a $25 entry and the other with the $4,4444 entry. Pricing is out already and it looks like the Short Game and Birdie are about double their usual size, and the Drive the Green is about three times bigger. If these contests are too big for your liking, you can always play in the secondary or tertiary contests. Check the lobby early in the week so you can come up with a new plan if necessary.

Once you have decided which contests you will be playing in, we need to decide how much leverage we want and how we’re going to get that leverage.

As I mentioned above, cumulative ownerships of winning lineups have been all over the map. I think you just have to take whichever path with which you are most comfortable. If you’re more of a contrarian player, I would shoot for 60%. If you like the chalk, you can shoot for 80%. And if you don’t feel compelled to go to either extreme, just shoot for our usual 60%-80% range. Even if you choose to go the chalky route, it’s always good to have some leverage plays mixed in, so be sure to have a few golfers under 10% at least and maybe even a couple sub-5% golfers.

As always, we have the same two places we turn to for leverage every week. The first is the ownership projections, where we will try to identify the chalk and then look for good pivots off the chalk. We can then look at the pricing; identify golfers that are priced too low and consider fading them because they will likely be over-owned and identify the golfers that are priced too high and give them consideration because the DFS community will try to avoid them.

I also think that most DFS players will be going with stars-and-scrubs lineups; most DFS players simply cannot help themselves and are always attracted to the top of the field. We can get leverage by building balanced lineups. Fading the top of the pricing is always risky, but if they stumble at all, you will be in a good spot.

Another thing we should consider is the trends. Touts and analysts love talking about trends, especially at the majors, and I suspect we will hear a lot about them this week. On the Inside Golf podcast last season, Steve Bamford identified three trends for identifying Open winners: a top 11 finish in one of the season’s previous majors, a strong record at the Open, and top 40 in the OWGR. Brian Harman didn’t fit the trend exactly (he was miserable at the majors leading up to The Open), but DFS players will look to these trends to identify golfers for their player pool and golfers that fit these trends will likely see a bump in ownership. It may be worth considering fading them. You can also look for golfers that just miss fitting the trends; they will still likely be a good play for the tournament, but they probably will not get the ownership bump. For a comprehensive list of trends, check out this article by the ultimate authority on major trends, Dave Tindall.

I haven’t seen anything yet (other than Rory being from Northern Ireland), but a hometown narrative is bound to pop up if any of the golfers happen to have grown up near Portrush. These golfers will likely see increased ownership due to their relationship with the course; you will have to decide if the extra steam is worth the familiarity with the course.

I think most DFS players will take a similar approach to identifying golfers for their player pool as I have; they will be looking for golfers that are well-rounded and have a strong history at The Open. You should be able to get a little different by targeting the bombers or targeting golfers that have not performed well at the Open or have not played in The Open. While Xander Schauffele had a strong history before his win and Brian Harman had a previous top ten at The Open and plodded his way to victory at Royal Liverpool, bombers like Rory McIlroy, Jon Rahm, and Cameron Young all scored top tens, demonstrating that the bombers can compete at Open venues. Collin Morikawa and Cameron Smith proved you do not need a strong record at The Open to be successful there. It is a riskier route to take, but it can pay off.

Once you’ve decided which contests you want to play and how you’re going to get leverage, you can start thinking about roster construction. So, turning to the Roster Construction Matrix, we have a strong field at a course that is probably medium in difficulty. The Roster Construction Matrix points us towards a stars-and-scrubs lineup. Given that stars have an exceptional record at The Open, I am inclined to go with the stars-and-scrubs build. Scottie Scheffler is priced up over 14k again, but the 5k range is back as well; so I think these lineups are viable even with Scottie.

It's been a tough season, so my plan this week is to use a little extra bankroll and focus on one of the bigger GPPs, probably the Drive the Green. I’ll probably be overweight with stars-and-scrubs lineups and possibly mix in a super stars-and-scrubs or balanced lineup. I’ll probably play a little contrarian since the contests are bigger. I’ll play the chalk that I like but I’ll shoot for cumulative ownerships of 60%-70%.

Now that we have a plan for the week, we can focus on the type of golfers we will target.

While we don’t have much data to work, we know enough about the course and Shane Lowry’s experience winning an Open Championship there to figure out what skills are needed to have success at Royal Portrush.

On his way to victory, Lowry led in both Strokes Gained: Off the Tee and Approach while hitting 62.5% of fairways and 79.2% of the greens in regulation. While I wouldn’t consider Lowry a bomber, he at least wasn’t losing strokes due to distance; he probably led the field due to the combination of above average accuracy and modest distance. Since he missed 20% of the greens he must have been sharp with his short game, and not giving too much back to the field when he missed. It’s exceedingly rare for somebody to putt poorly and win a tournament, so I think we can assume he was putting well.

In general, I think this mean we’re looking for ballstrikers; golfers that keep the ball in play off the tee, either in the fairway or close enough that they are able to recover, pound greens with their irons, have a strong short game, and are comfortable putting on Open-style greens. All-around quality golfers that can be successful no matter how the course plays (as opposed to specialists like bomb-and-gougers or birdie makers).

Links golf is also such a rare occurrence for PGA Tour golfers, I think we also want to look out for golfers with experience at The Open and the Scottish Open. Links golf can be a mental test as much as it a physical one. The course setup can change day-to-day depending on the weather, particularly the wind, and the wind conditions can change hour-to-hour or even hole-to-hole (the routing of Portrush switches direction with every hole, so the influence of the wind will be different on each hole) . The best way to determine if a golfer can manage the ever-changing conditions of a links course is to see how they have performed at links courses.

As usual, I will start my process by building my course fit model and putting together a Recent Form and Event History spreadsheet. I will use my model to target golfers that are accurate off the tee, strong with their irons, clean around the green, and comfortable putting on slow greens.

Instead of Course History, I will put together an Event History spreadsheet this week. I’m doing this for two reasons. First, we only have one year of relevant Course History data to work with (2019). Two, because the Open Championship is always played at a links course, Event History is a good indication of how well players perform on these types of courses. Since 2012, all but two winners of the event, Cameron Smith and Collin Morikawa, had previously finished in the top 10 at least once. Andy Lack mentioned on his podcast that the best comparisons for Portrush are Liverpool (2023) and St. George’s (2021), so I will be paying close attention to those years too.

Here are the course fit statistics that I will use (last 100 rounds):

Off-the-tee:

Strokes Gained: Off-the-Tee: A staple in my model week after week; I will use other off-the-tee statistics to fit the model to individual courses. Scoring at Portrush will start with sound off-the-tee play, so we want strong drivers of the ball this week. I will, therefore, put a little more emphasis on these statistics this week.

Fairways Gained: Success at Royal Portrush starts with keeping the ball in play. The fairways might not necessarily be difficult to hit, but accuracy was below the tour average last time we saw Portrush. Golfers playing from the fairway will miss all the trouble lurking away from the short grass and have the best chance to put their approach shots on the greens.

Approach:

Strokes Gained: Approach: A staple in my model week after week, on a course with deep bunkers and tricky chip shots around the green, I want to make sure that I am rostering golfers that will hit a lot of greens. I will look at this statistic on courses over 7,200-7,400 yards.

Greens in Regulation: With contours designed to repel and filter errant approach shots into greenside bunkers and collection areas, I think most golfers will not take on risky pin locations and will play towards the middle of the green.

Overall Proximity: Any time we have heavily undulated greens, golfers do themselves a huge favor by landing their approach shot close to the hole and giving themselves a realistic look at birdie. We don’t have any proximity range data though, so I will just go with general proximity. If I see anything that suggests one proximity range will be more important than the others, I will add it to the model.

Around the Green:

Strokes Gained: Around the Green: Only 13 golfers hit 70% of greens last time they were at Portrush, so golfers will have to rely on a strong short game to stay in contention.

Putting

Strokes Gained: Putting on Slow Greens: I usually specify a surface type for putting statistics, but the fescue isn’t one of the options on Fantasy National and we don’t get Strokes Gained: Putting statistics from past Open Championships, so I will just stick with slow greens. Most PGA Tour golfers are not accustomed to putting on the slow greens of links courses. I want to roster golfers that have shown an ability to putt on greens that could reach single digits on the stimp.

Scoring:

Strokes Gained: Total at The Open Championship: I don’t usually include Course History, or Event History in this case, in my model, but I really want to lean into the notion that golfers with previous success at The Open are more likely to perform well again.

Par 5 Scoring: The three best scoring opportunities on the course are the par 5s, golfers better be prepared to take advantage of them.

Par 4 Scoring 400-450 yards: Six of the holes on the course fall into this range and it was on these holes that golfers in the top ten in 2019 were really able to separate themselves from the pack. Making pars and picking up an occasional birdie on these holes should lead to a chance at taking hold of the Claret Jug.

After building my model, I usually have a few other statistics that I will look at to help make my determinations. This week, I will look at Good Drives Gained at Courses with Short Rough, Birdies or Better Gained, and Bogey Avoidance. If the winds pick up, I will also make sure to look at Strokes Gained: Total in the Wind.

Golfers will inevitably miss some fairways; I want to roster golfers that are capable of getting the ball on the green when they play from the rough. The rough will be short within two yards of the fairway and becomes a gnarly mess after that, so we really only need to concern ourselves with how golfers play from the short rough since they will be in serious trouble otherwise.

As of now, under the current conditions, I think the winning score will approach 15 under par again, so I will be looking for golfers that can make a lot of birdies.

Even though conditions will likely permit good scoring opportunities, there will be instances where golfers will struggle to make par (a missed fairway or green will do the trick). Golfers need to limit how many strokes they give up when they get into tough spots.

I will also build a model that includes statistics that are only available using The Rabbit Hole on Betsperts.com. For The Open, I am interested in SG: Off-the-Tee at courses with a High Missed Fairway Penalty, Distance from the Edge of the Fairway, Stokes Gained: Approach, Greens in Regulation %, Strokes Gained: Around the Green at UK Courses, Strokes Gained: Putting at UK Courses, SG: Total on Links courses, Strokes Gained: Total at UK/Ireland Courses, and Par 5 Birdie or Better %.

In short, I am looking for golfers that are well-round; golfers that keep the ball in play off the tee, are excellent with their irons, keep it clean around the greens and putt well on slow greens. I would rather see decent statistics across all four statistical categories than exceptional statistics in one or two categories but deficient in one category. I’ll also look for golfers that have played well at links courses in the past. The statistics that I will focus on to start my player pool are Fairways Gained, Strokes Gained: Approach, Strokes Gained: Putting, and Open history. I will also focus on the analogues from my Rabbit Hole model.

Before I wrap this up, I want to remind you again that DFS lock for these overseas events should be right around midnight in the Central time zone. We can put in all the work, but it’s all for naught if we don’t remember to set our lineups.

That’s all I have for now, be sure to follow me on Twitter (@glzisk) for any updates.

Have a great week!